W. B. Yeats and Yoga

Exploring W.B. Yeats' Fascination with Yoga Philosophy and Patanjali's Aphorisms - By Hannah Comer

Reading time: 4 minutes

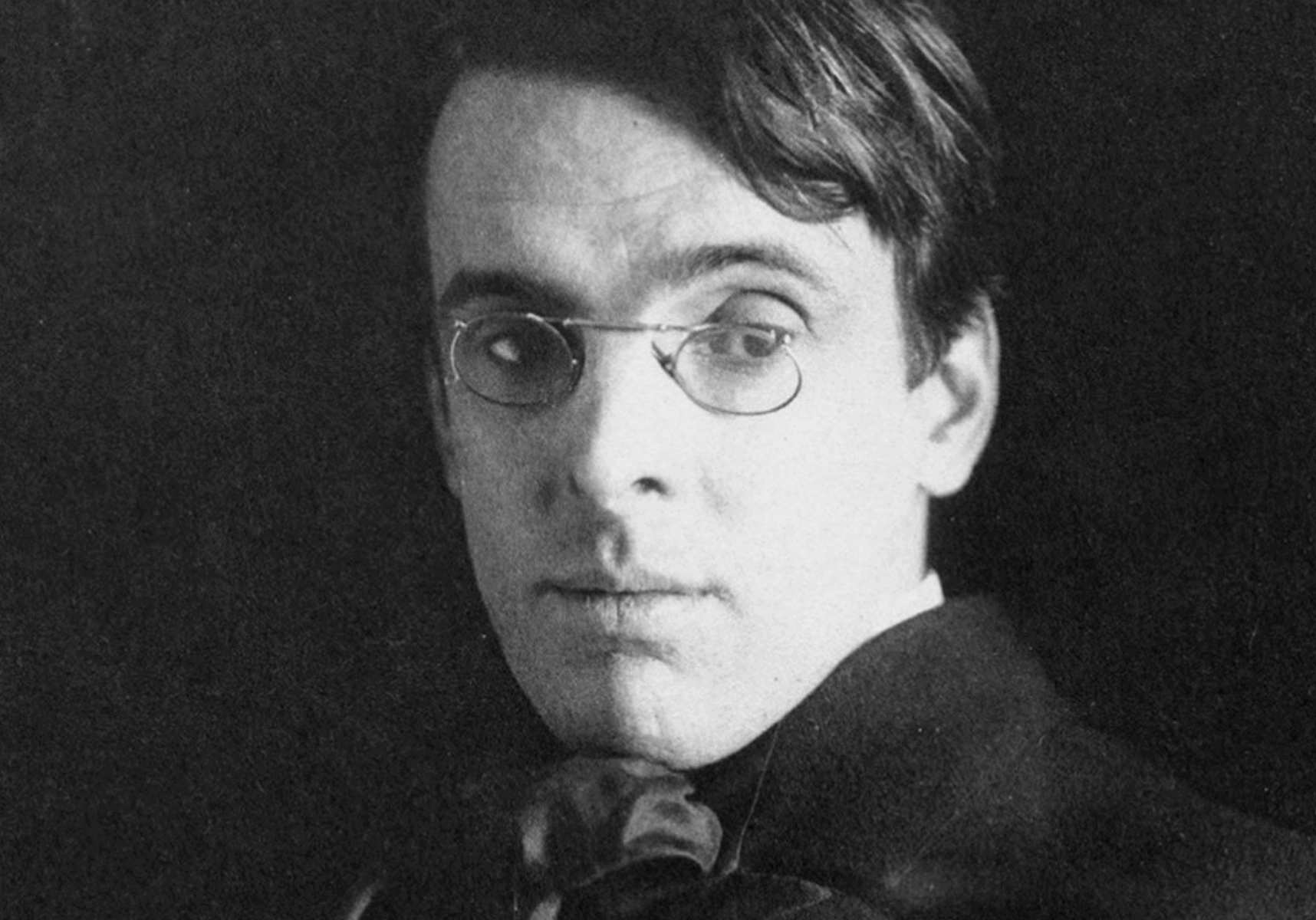

In his introduction to the Aphorisms of Yoga by Bhagwān Shree Patanjali (1938), W. B. Yeats (1865-1939), the renowned poet, dramatist and senator for the Irish Free State, describes himself as ‘engaged in that endless research into life, death, God, that is every man’s revery’.[i]

Published in the year before his death in 1939, Yeats’s statement outlines his lifelong exploration of, and fascination with, global philosophies and mythologies, religions, spiritualism and occultism, which constituted the creation of his own personal belief system and philosophic thought.

Yeats’s exploration and study of ancient Indic wisdom and yoga philosophy was of both a creative and spiritual interest, expanding and challenging his notions of the Self, the Soul and Divinity, which he explores throughout his own poetic, mythological, and spiritual works.

Yeats’s long-term interest in yoga philosophy and meditation was rekindled in the 1930s, especially through his friendship and collaboration with Shri Purohit Swami, where they found mutual interest in mystical principles. Shri Purohit Swami (1882-1941) was a Hindu monk, philosopher and poet who travelled from India to England in 1931, and was introduced to Yeats by their mutual acquaintance, the poet, writer and artist, Thomas Sturge Moore.

At the time, Purohit Swami was writing an autobiography, a biographical account of his teacher, Shri Bhagwan Hamsa, and his own poetry, as well as lecturing on religious and philosophical texts such as The Bhagavad Gītā. Moore had sent Yeats a copy of Purohit Swami’s memoir The Autobiography of an Indian Monk, detailing his life in India. Yeats called the book ‘a masterpiece’.[ii]

This began a collaboration between Yeats and Purohit Swami which would result in four important works; the two memoirs, The Autobiography of an Indian Monk: His Life And His Adventures (1932) and The Holy Mountain: Being the Story of a Pilgrimage to Lake Manas and of Initiation on Mount Kailas in Tibet (1934); and two translations, The Ten Principal Upanishads (1937) and the Aphorisms of Yoga (1938). Yeats helped translate these two texts into English and provided introductions to all four works.

Most of the translation for both The Upanishads and the Aphorisms of Yoga took place in Majorca, between 1935-36, as Yeats was unable to travel to India, as originally planned, due to ill health. As it is widely regarded as the authoritative text on yoga, this article focuses on Yeats’s introduction to The Aphorisms of Patanjali, in which he explores his own understanding of yoga. He suggests his prior familiarity with the text before working on the translation, claiming that ‘some years ago I bought The Yoga-System of Patanjali, translated and edited by James Horton Woods’ and to ‘know nothing but the novels of Balzac and the aphorisms of Patanjali’.[iii]

Throughout his writings and letters, Yeats reflects upon, and grapples with, the teachings and wisdom of Patanjali’s aphorisms or sutras. Their 1938 edition of the Aphorisms of Patanjali is also accompanied by illustrations of several yogic postures, included at the end of the book. In his introduction to the text, Yeats traces what little information is known of Patanjali from scholarship, and from the composition of the Yoga Sutras, which is believed to have been compiled between 200-500 BCE.

Yeats describes Patanjali as a sage who ‘sought truth not by the logic or the moral precepts that draw the crowd, but by methods of meditation and contemplation that purify the soul.’[iv] As Yeats notes, Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras defines yoga by meditation; the goal of yoga is ‘controlling the activities of the mind’ (Sutra I.2). [v] The Yoga Sutras details the eight limbs of yoga (Yamas, Niyamas, Asana, Pranayama, Pratyahara, Dharana, Dhyana and Samadhi) as the yogic path to follow and live by.

In the Yoga Sutras, the science and philosophy of yoga is explained: its aims, practices, potential obstacles and their removal, and results obtained from these practices. Following these principles leads the practitioner towards enlightenment, transcendence, freedom and peace. Throughout the rest of his introduction, Yeats outlines yogic, Hindu and Buddhist processes of enlightenment, attaining Samadhi, a state of deep meditative consciousness, ‘where the soul, purified of all that is not itself, comes into possession of its own timelessness’.[vi]

At this stage, the meditator transcends the ego-conditioned mind and the Self, experiencing supreme bliss and pure consciousness. Yeats states that in ‘the Upanishads and in Patanjali the Self and the One are reality’; in the state of Samadhi, human consciousness, or the true Self, becomes one with divine or cosmic consciousness.[vii]

The word ‘Yoga’ itself means ‘union’ – the union of the body, mind, and soul; Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras are guides to both achieving and remembering that union, Samadhi.

In the conclusion of his introduction, Yeats adopts literary and spiritual examples to further describe the state of Samadhi, with Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s protagonist, Faust, becoming a model for the meditator and the processes of enlightenment. In Goethe’s play Faust (1808 and 1832), Faust makes a deal with Mephistopheles (a demon), who will serve him for life, if in return, Faust will serve him in the afterlife.

In order to avoid his fate, Faust makes a bet – if Mephistopheles can grant him an experience of blissful transcendence on earth – he will die and serve him in the afterlife. Yeats argues that both Goethe and Faust sought to experience ‘a moment acceptable to reason’ where ‘thoughts and emotions could find satisfaction or rest’, seeking truth and unity in their work and philosophy, but they both failed, because neither

Goethe nor his audience knew of a science or philosophy that sought a different level of consciousness.[viii] In terms of the spiritual examples, Yeats links an ‘impure’ Samadhi to the Christian mystics and philosophers, Emanuel Swedenborg and Jakob Bohme, and to later psychical research, experiences of clairvoyance and vision, described as ‘a series of spiritual states from man to God’.[ix]

In Yeats’s introduction to Patanjali’s text, the practice of yoga is defined as a spiritual discipline that leads the practitioner to self-understanding, unity, enlightenment, the transcendence of the Self and the realisation of the Soul.

[i] W. B. Yeats, ‘Introduction’ in Aphorisms of Yoga by Bhagwān Shree Patanjali, translated by Shree Purohit Swami and W. B. Yeats (London: Faber & Faber 1938), pp.11-21 (p.11).

[ii] W. B. Yeats, ‘To George Yeats [Dobbs], February 8, 1932’, in W. B. Yeats & George Yeats: The Letters, ed. by Ann Saddlemyer (New York: Oxford University Press 2011), p. 296.

[iii] W. B. Yeats, ‘Introduction’ in Aphorisms of Yoga, p.11 and W. B. Yeats, ‘Introduction’ in Shri Purohit Swami, The Holy Mountain: Being the Story of a Pilgrimage to Lake Manas and of Initiation on Mount Kailas in Tibet (London: Faber & Faber 1934), pp.11-41 (p.11).

[iv] W. B. Yeats, ‘Introduction’ in Aphorisms of Yoga, p.15.

[v] Aphorisms of Yoga by Bhagwān Shree Patanjali, translated by Shree Purohit Swami and W. B. Yeats, p. 25.

[vi] W. B. Yeats, ‘Introduction’ in Aphorisms of Yoga, p.15.

[vii] Ibid, p.16.

[viii] Ibid, pp.18-19.

[ix] Ibid, p.20.