Sāṃkhya 101

Feminine and masculine, matter and consciousness, shadow and light – one cannot exist without the other. The power of duality lies at the heart of Samkhya philosophy which attempts to explain life in all its manifestations. The fundamental premise is that liberation comes through knowledge and knowledge through experience, but while we’re on the journey gathering both, we might fall prey to the mythical Sirens of attachment and become bound… - By Anna Freud

Reading time: 5 minutes

Samkhya (also spelled Sankhya) is one of the six darshanas, or schools of thought in Indian philosophy concerned with the ultimate meaning of life and offering guidance on how best to live it. Although there is no historical record of its origin, it is attributed to ancient sage Kapila who was considered an incarnation of Lord Vishnu. The teachings were first passed down orally through his disciples before finally being summarised by Ishvarakrishna in his Samkhya Karika around 2nd century CE. This text and its commentaries had become foundational to studying Samkhya, and had a great impact on many writers on yoga, including Patanjali. So, what is it about?

The core idea is that duality underlies all life, its manifestations and processes; it is a dance of the two fundamental principles: purusha (consciousness) and prakrti (matter). The purpose of incarnation in any form is evolution and once in a human body – enjoyment and emancipation (you read that right). Liberation is defined as release from the cycle of rebirths (samsara) and happens when the ultimate realisation of the nature of the universe has been achieved through discriminative discernment between consciousness and matter, the 25 tattvas (principles) and the mechanics of manifestation. This knowledge is gained through experience using the tools of perception (the senses), inference (reasoning) and valid testimony (a qualified person’s teaching) – in this order. Life is a learning journey and what we need to navigate most is our attachments.

Purusha

One of the two unmanifest tattvas, the indweller of the body. Consciousness or awareness, it is the sentient but passive aspect of creation, the observer. Omnipresent and timeless. Referred to as the ‘Supreme Self’, it incarnates in a body to enjoy and learn from experience in order to eventually realise its own true nature. However, it is incapable of action and needs prakrti to be able to achieve this goal.

Prakrti

The second unmanifest tattva, from which the body forms. Nature or matter, it is insentient but active, the doer. Omnipresent and timeless. It does not need to realise itself but allows purusha to work through it. It is comprised of three attributes called gunas: sattva (light), rajas (movement) and tamas (stability). Perfectly balanced in its formless state, it loses its equilibrium when in contact with purusha and becomes activated, which leads to manifestation of the phenomenal world.

Gunas

The three aspects of prakrti, namely sattva, rajas and tamas. Sattva means light and has the nature of pleasure; rajas corresponds to movement and feelings of pain; and tamas relates to stability but also heaviness and delusion. The three gunas always work together as they have distinct roles to play and complement one another. As Kārikā 12 explains, “they are adapted to illuminate, to activate and restrain. They mutually suppress, support, produce, consort and exist” (Bawra, 2018). All creation consists of gunas, their varying proportions giving rise to different forms as well as changes within the same form. In our human experience, the predominance of sattvic energy presents as calm, quiet and pleasant nature; rajasic as passionate and active; and tamasic as dull, lethargic and stable. As the gunas fluctuate so does our state of mind, and the quality of our thoughts and projections is determined by which guna is dominant in a given moment.

Tattvas

The process of manifestation is explained through 25 tattvas, or principles, underlying cosmic order. When unmanifest Nature (prakrti) comes in contact with Spirit (purusha), the first creation in the form of intellect (mahat) takes place. Following are ego (ahamkara), mind, five subtle elements (sound, touch, form, taste and smell), five organs of sense (ear, skin, eye, tongue and nose), five organs of action (tongue, hands, feet, organs of procreation and excretion), and the five gross elements (earth, water, fire, air and space). All these serve as tools for purusha as indweller of the body to realise its own true nature. Once it has gathered enough information through experience and can discriminate between manifest, unmanifest and the Knower, it is released from the cycle of rebirths (samsara).

To conclude, Samkhya presents the relationship between purusha and prakrti like that of the lame man and the blind man – Spirit has the ability to contemplate but not act, and Nature is endowed with the power of action but not contemplation. Each needs the other one to reach the destination. Life is an opportunity to consciously experience divine Nature and realise oneness with the Supreme Self. And misidentification and attachments are what keeps the wheel of samsara spinning.

___________________________________________

References:

Bawra, B.V. (2018), Sāṃkhya Kārikā with Gaudapādācarya Bhāsya. Revised Edition. Brahmrishi Yoga Publications.

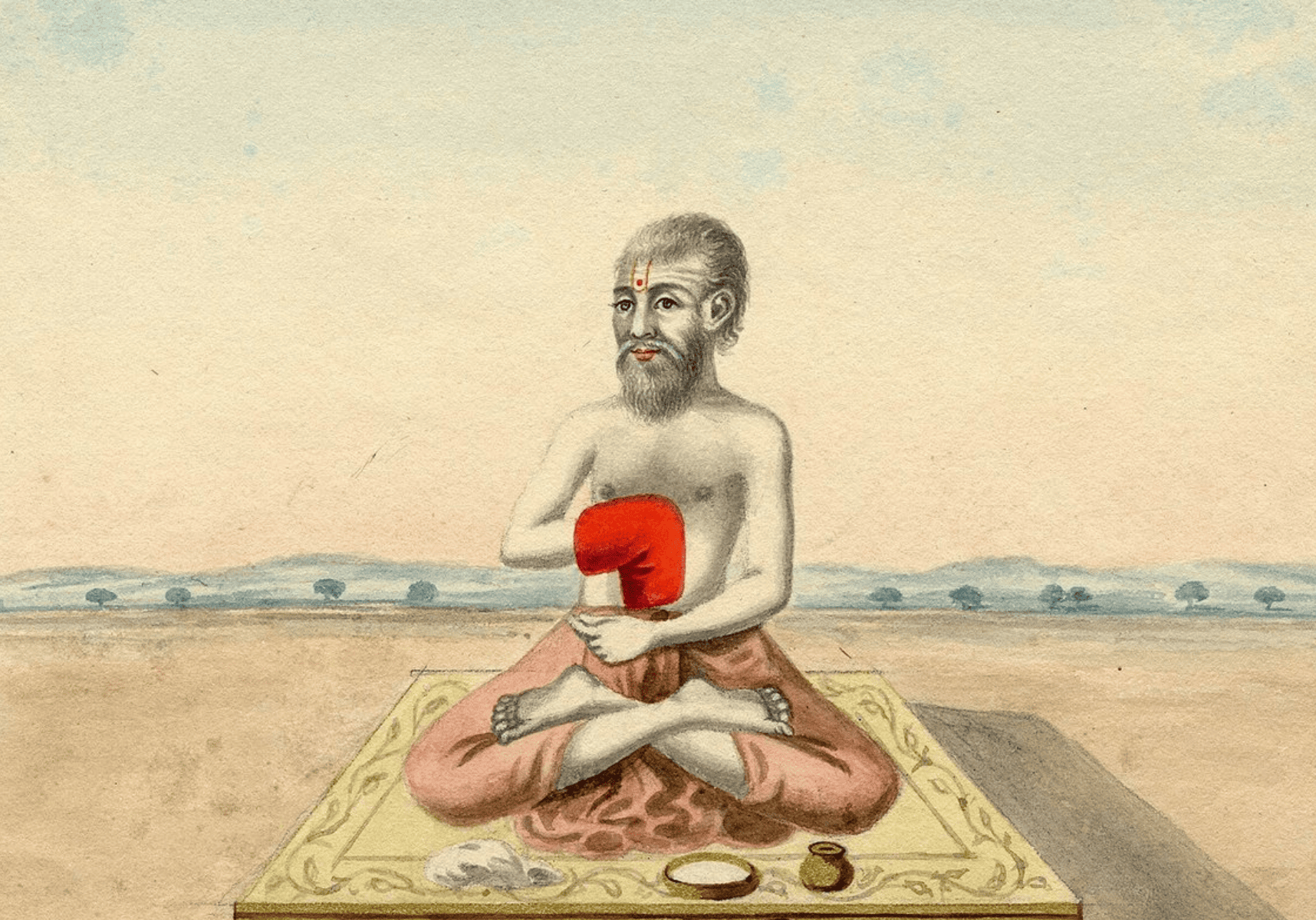

Image: Capila, 19th c., The British Museum.